The Real Estate Industry’s Digital Infrastructure Has Evolved Far Beyond Its Original Purpose—And Not Everyone Is Happy About It

When Multiple Listing Services (MLSs) were first conceived, their mission was elegantly simple: to create a neutral marketplace where competing brokerages could share property listings for the benefit of buyers and sellers. This cooperative spirit transformed real estate from a fragmented, inefficient market into the interconnected system we know today.

But according to HomeServices of America CEO Chris Kelly, that original mission has been compromised. “The listing platforms have not been neutral actors in this evolution. Shifting standards and closed-door policy decisions have created understandable concern among brokerages,” Kelly recently wrote in an op-ed for Inman News.

This sentiment reflects a growing tension within the real estate industry: MLSs have evolved from simple listing repositories into technology powerhouses that increasingly compete with the very brokerages they were designed to serve.

Generated by ChatGPT (DALL·E)

The Great Expansion: From Listings to Everything Else

Today’s MLSs bear little resemblance to their cooperative origins. What began as basic listing databases have morphed into comprehensive technology platforms offering everything from CRM systems to lead generation tools—services that directly compete with brokerages’ core business functions.

The transformation raises fundamental questions about neutrality and purpose. When an MLS develops technology solutions that compete with its member brokerages, can it truly remain an impartial facilitator? When it distributes listings to referral-only platforms that don’t represent actual buyers and sellers, does it serve the market’s best interests?

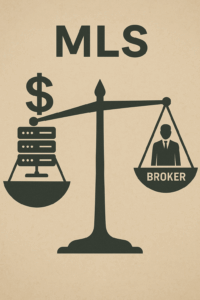

Perhaps most concerning for brokerages is the financial dimension. MLSs have leveraged their monopolistic position to charge premium fees for services – amassing substantial reserves while brokerages struggle with thin margins. These funds often flow to subsidize Realtor Associations, further blurring the lines between supposedly neutral market infrastructure and advocacy organizations.

The Data Dilemma: Profiting from Broker-Generated Content

One of the most contentious issues involves data licensing. MLSs routinely license listing data to capital markets and third-party platforms, generating significant revenue streams. Yet the listing brokers who create this valuable content—through photography, descriptions, and market intelligence—see none of these proceeds.

This arrangement would be questionable in any industry, but it’s particularly problematic in real estate, where listings represent brokers’ primary marketing assets. Imagine a newspaper selling its journalists’ articles to competitors without sharing the revenue, or a shopping mall monetizing a retailer’s product listings without compensation.

The practice raises questions about who truly owns listing data and whether MLSs should profit from content they don’t create.

The Neutrality Question: Leveling Whose Playing Field?

MLSs often justify their expanded role by invoking the need to “level the playing field.” But level for whom? When MLSs develop technology tools, they’re not leveling the field between brokerages—they’re creating new competitors while maintaining their privileged position as the sole source of listing data.

Kelly noted that MLS meetings “used to be all about local discussions” but “these conversations have really turned national in scale,” reflecting how these supposedly local, cooperative organizations now wield industry-wide influence over how brokerages can operate their businesses.

This shift represents what many brokerages see as “a bridge too far”—MLSs are no longer neutral facilitators but active participants shaping competitive dynamics in ways that may not serve brokers or consumers.

A Radical Solution: Back to Basics

The frustration has led some industry leaders to propose dramatic solutions. The most radical: eliminate IDX (Internet Data Exchange) entirely. Under this scenario, brokers would only advertise their own listings on their websites, while the comprehensive MLS compilation would remain exclusively available to consumers working with licensed agents who are subscribers to the MLS under a buyer broker agreement.

Such a change would fundamentally alter real estate marketing, forcing consumers to work directly with agents to access complete market information. While this might seem regressive in our digital age, proponents argue it would restore the proper role of professional representation while eliminating MLSs’ ability to commoditize listing data.

A less dramatic but still significant reform would restrict MLSs to their core functions: maintaining the listing database and providing tax/property information. This “MLS plus tax solution” approach would eliminate competitive conflicts while preserving the cooperative benefits that made MLSs valuable in the first place.

The Technology Paradox

The irony is that technology—which MLSs cite as justification for their expansion—could actually enable a return to more focused roles. Modern APIs and data standards make it easier than ever for specialized companies to provide technology solutions while MLSs maintain listing databases.

Rather than trying to be all things to all people, MLSs could focus on what they do best: maintaining accurate, comprehensive property databases with reliable uptime and robust security. Brokerages could then choose from competitive technology providers for CRM, lead generation, and other business tools.

Generated by ChatGPT (DALL·E) | Image ID

The Path Forward: Cooperation Without Competition

The real estate industry’s cooperative foundation remains one of its greatest strengths. Unlike other sectors where incumbents typically resist sharing information, real estate has thrived precisely because competitors agreed to share listings for mutual benefit.

But cooperation shouldn’t mean capitulation. As Kelly’s comments suggest, the industry needs an honest conversation about MLSs’ proper role in the modern real estate ecosystem. Should they remain neutral facilitators, or should they continue evolving into comprehensive technology platforms that compete with their own members?

The answer may determine whether real estate maintains its cooperative spirit or fragments into competing data silos—each controlled by technology companies with little stake in the industry’s long-term health.

For brokerages, the stakes couldn’t be higher. Their listings represent their primary marketing assets, their technology needs are increasingly sophisticated, and their profit margins remain under constant pressure. The last thing they need is competition from the very organizations they fund to facilitate cooperation.

The solution isn’t to abandon MLSs but to restore their original mission: providing neutral, reliable infrastructure that serves all market participants equally. Whether the industry can achieve this reset—or whether MLSs will continue their mission drift—remains to be seen.

What’s certain is that the current trajectory isn’t sustainable.

When neutral facilitators become competitive threats, cooperation inevitably gives way to conflict.

And in that environment, everyone loses—brokers, MLSs, and ultimately, the consumers they all claim to serve.